Judges Opinions Public Notices, — December 9, 2020 11:28 — 0 Comments

Public Notices, December 9, 2020

Volume 58, No. 19

PUBLIC NOTICES

DECEDENTS’ ESTATES

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Jason R. Ulshafer, Executor for the Estate of William J. Zimmerman, Deceased, v. HCR Manorcare, Inc., et al.

NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that Letters Testamentary or of Administration have been granted in the following estates. All persons indebted to the said estate are required to make payment, and those having claims or demands to present the same without delay to the administrators or executors named.

FIRST PUBLICATION

ESTATE OF JANE L. SULTZBAUGH, late of Palmyra Borough, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executor.

Earl R. Beyer, Executor

Kevin M. Richards, Esquire

P.O. Box 1140

Lebanon, PA 17042-1140

ESTATE OF HARVEY J. BOMBERGER, late of the Borough of Myerstown, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executor.

Carl H. Bomberger, Executor

418 Westfield Court

Lititz, PA 17543

Kenneth C. Sandoe, Esquire

Steiner & Sandoe

36 West Main Avenue

Myerstown, PA 17067

ESTATE OF KENNETH J. NELSON, late of the Borough of Myerstown, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executor.

Rock A. Nelson, Executor

1260 Ash Lane

Lebanon, PA 17042

Timothy T. Engler, Esquire

Steiner & Sandoe

36 West Main Avenue

Myerstown, PA 17067

ESTATE OF DAVID B. FAHNESTOCK, late of North Londonderry Township, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Co-Executors.

Wendy Jo Fahnestock, Co-Executor

Dane A. Fahnestock, Co-Executor

Reilly Wolfson Law Office

1601 Cornwall Road

Lebanon, PA 17042

ESTATE OF NANCY M. SNYDER, late of North Lebanon Township, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Co-Executors.

John L. Snyder, Co-Executor

Susan M. Comp, Co-Executor

Reilly Wolfson Law Office

1601 Cornwall Road

Lebanon, PA 17042

ESTATE OF LORRAINE H. ZUCK, late of South Lebanon Township, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Co-Executors.

Norma J. Swanger, Co-Executor

Dale T. Zuck, Co-Executor

Gerald J. Brinser, Esquire

- O. Box 323

Palmyra, PA 17078

ESTATE OF ROBERT W. FIDLER, late of the City of Lebanon, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executor.

Dodie Jill Houtz, Executor

Reilly Wolfson Law Office

1601 Cornwall Road

Lebanon, PA 17042

ESTATE OF ROBERT A. MEYER, SR., late of the Borough of Myerstown, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executors.

Robert A. Meyer, Jr., Executor

31 Georgie Lane

Richland, PA 17087

Steven T. Krall, Executor

202 S. Railroad Street

Myerstown, PA 17067

Timothy T. Engler, Esquire

Steiner & Sandoe

36 West Main Avenue

Myerstown, PA 17067

ESTATE OF CHRISTINE K. SCHOTT, late of Cornwall Borough, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executor.

Robert D. Lutz, Executor

Reilly Wolfson Law Office

1601 Cornwall Road

Lebanon, PA 17042

ESTATE OF JENNIE E. HORSTICK, late of North Londonderry Township, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters of Administration have been granted to the undersigned Administrator.

Ronald C. Horstick, Administrator

528 Douglas Road

Hummelstown, PA 17036

Joseph M. Farrell, Esquire

201/203 South Railroad Street

P.O. Box 113

Palmyra, PA 17078

ESTATE OF GREGORY L. TRUMP, late of the Township of Heidelberg, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executor.

Nicholas Trump, Executor

Young and Young

44 S. Main Street

P.O. Box 126

Manheim, PA 17545

SECOND PUBLICATION

ESTATE OF KARL PAUL ADEY, late of the borough of Palmyra, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, died 09/24/2020. Letters of Administration have been granted to the undersigned Administratrix.

Karen B. Adey, Administratrix

George W. Porter, Esquire

909 Chocolate Ave.

Hershey, PA 17033

ESTATE OF PAUL G. CRUM, late of the Township of Swatara, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executor.

Brion Crum, Executor

1789 Grace Avenue

Lebanon, PA 17046

Kenneth C. Sandoe, Esquire

Steiner & Sandoe, Attorneys

36 West Main Avenue

Myerstown, PA 17067

ESTATE OF ADAM KLINE, JR., late of Heidelberg Township, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executor.

Kim M. Whitmoyer, Executor

111 Mountain Trail Road

Newmanstown, PA 17073

Timothy T. Engler, Esquire

Steiner & Sandoe, Attorneys

36 West Main Avenue

Myerstown, PA 17067

ESTATE OF BRENDA J. GALLAGHER, late of North Lebanon Township, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executrix.

Mary Taylor, Executrix

Charles A. Ritchie, Jr., Esquire

Feather and Feather, P.C.

22 West Main Street

Annville, PA 17003

ESTATE OF HARVEY F. RITTLE, A/K/A HARVEY FRANKLIN RITTLE, late of the City of Lebanon, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executor.

Robert L. Rittle, Executor

Kevin M. Richards, Esquire

P.O. Box 1140

Lebanon, PA 17042-1140

ESTATE OF LEROY L. LEHMAN, late of the City of Lebanon, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executor.

John S. Kunder, Jr., Executor

Kevin M. Richards, Esquire

P.O. Box 1140

Lebanon, PA 17042-1140

ESTATE OF MARY B. WILLMAN, late of Annville Township, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executrix.

Kathleen M. Minnich, Executrix

Kevin M. Richards, Esquire

P.O. Box 1140

Lebanon, PA 17042-1140

ESTATE OF PATRICIA R. CARVELL, late of South Londonderry Township, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased (died September 18, 2020). Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executor.

Michael C. Carvell, Executor

940 Carriage House Court

Hershey, PA 17033

Peter R. Henninger, Jr., Esquire

Jones & Henninger, P.C.

339 W. Governor Rd., Ste. 201

Hershey, PA 17033

THIRD PUBLICATION

ESTATE OF ARTHUR M. KELLER, JR., late of North Lebanon Township, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executrix.

Kristin M. McLerran, Executrix

312 S. 13th Street

Lebanon, PA 17042

Stephanie DiVittore, Esquire

Barley Snyder

213 Market Street, 12th Floor

Harrisburg, PA 17101

ESTATE OF RONALD W. WISE, late of Jackson Township, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executrix.

Donna M. Borgnis, Executrix

Cheryl J. Allerton, Esquire

Allerton, Bell & Muir P.C.

1095 Ben Franklin Highway East

Douglassville, PA 19518

ESTATE OF JAQUELINE W. MOYER, late of the Borough of Myerstown, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters of Administration have been granted to the undersigned Administrator.

Mary J. Warner, Administrator

Lindsay M. Schoeneberger, Esquire

Russell, Krafft & Gruber, LLP

108 West Main Street

Ephrata, PA 17522

ESTATE OF ARLENE M. TILBERRY, late of the Borough of Palmyra, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, died 10/28/2020. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executrix.

Cathy L. Repko, Executrix

George W. Porter, Esquire

909 E. Chocolate Ave.

Hershey, PA 17033

ESTATE OF MILDRED L. FARVER, late of the Borough of Palmyra, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executor.

S. Scott Farver, Executor

221 E. Broad Street

Palmyra, PA 17078

David R. Warner, Jr. Esquire

Buzgon Davis Law Offices

P.O. Box 49

525 South Eighth Street

Lebanon, PA 17042

ESTATE OF EVA W. BRUBAKER, late of the Borough of Richland, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, deceased. Letters Testamentary have been granted to the undersigned Executor.

Richard L. Brubaker, Executor

491 W. Lincoln Avenue

Myerstown, PA 17067

Kenneth C. Sandoe, Esquire

Steiner & Sandoe

36 West Main Avenue

Myerstown, PA 17067

JUDGES OPINION

Jason R. Ulshafer, Executor for the Estate of William J. Zimmerman, Deceased, v. HCR Manorcare, Inc., et al.

Civil Action-Law-Negligence-Nursing Home Care-Wound Care-Motion in Limine-Exclusion of Evidence-Probative Value-Prejudice-Expert Testimony-Frye Test-Use of Terms-Hearsay-Official Records-Nursing Home Survey Reports-Registered Nurse as Expert-Bifurcation of Trial

William J. Zimmerman (“Decedent”), was a resident at Defendant’s facility after he had been diagnosed with cellulitis and monoarthritis. Decedent developed pain and tenderness of his right foot and a left foot blister while a resident at Defendant’s facility. Following left leg amputation below the knee, Decedent passed away in his home. Jason R. Ulshafer, Executor of Decedent’s Estate, filed a Complaint asserting that Defendant neglected promptly to diagnose and to address Decedent’s foot wound, which led to his leg amputation and death. Defendant filed Pretrial Motions in Limine seeking various evidentiary rulings prior to trial.

- Pa.R.E. Rule 403 provides that the court may exclude relevant evidence if its probative value is outweighed by unfair prejudice, confusion, undue delay or needless presentation of cumulative evidence.

- Unfair prejudice supporting exclusion of relevant evidence means that the evidence tends to suggest that a decision be made on an improper basis or to divert the jury’s attention away from its duty of weighing the evidence impartially.

- In weighing the probative value versus the prejudicial effect of evidence, the court’s analysis requires a fact intensive, context specific inquiry.

- In light of the limited insight possessed by the Court of the evidence that will be presented at trial, the Court will not adjudicate any objections based upon the prejudicial impact of evidence in advance of trial.

- Under Frye v. United States, 293 F. 1013 (D.C. Cir. 1923), the Court concluded that scientific evidence should be accepted in a courtroom only where the proffered scientific methodology has gained general acceptance in the particular field to which it belongs.

- The Frye test was developed to prevent expert testimony based upon fraudulent scientific principles, not to prevent experts from rendering opinions that may have suboptimal factual support.

- Since the expert offered by Plaintiff has a lifetime of experience dealing with wound care in the context of the nursing home environment and has familiarity with the consequences of failing properly to treat wounds, Defendants’ Motion to exclude the evidence offered by that expert will not be allowed under Frye.

- Plaintiff will not be prohibited from using terms at trial such as “abuse” and “neglect” on the basis that the words are inflammatory, as they are descriptive and defined by federal regulations governing long term care facilities and counsel may employ oratory flare in pursuing a client’s cause.

- Generally, speaking, out-of-court statements by a nontestifying witness are considered to be inadmissible hearsay.

- Official records are an exception to the prohibition against hearsay.

- Nursing Home Survey Reports completed by the Pennsylvania Department of Health are official records that are not barred from the prohibition against hearsay.

- The evidence of understaffing and insufficient care at a nursing home relates to all residents of the nursing facility, including a resident who passed away, and the effects of understaffing specifically may be connected to a decedent’s care.

- Title 40 P.S. § 1303.512 provides that an expert testifying on a medical matter including standard of care, risks and alternatives, causation and the nature and extent of injury must possess an unrestricted physician’s license in any state or the District of Colombia or be engaged in or retired within the previous five (5) years from active clinical practice or teaching.

- A registered nurse is qualified to provide testimony regarding the expected standard of care applicable to Defendant, not to render an opinion about whether Decedent’s leg amputation and subsequent death causally were related to any breach of the nursing standards attributable to Defendant.

- To authenticate a photograph at trial, testimony must be presented by any individual that the photograph fairly depicts the scene as the witness remembers it.

- A court possesses broad discretion with respect to how a case efficiently and fairly should be presented to a jury.

- Pa.R.C.P. Rule 213 permits the court to divide a trial into phases that can be presented separately to a jury.

- A joint trial on negligence and punitive damages will not be permitted, as the Court will permit a supplemental phase pertaining to punitive damages only if the jury responds that Defendant’s conduct could be characterized as outrageous after the primary stage.

- Plaintiff’s claims of professional and corporate negligence will not be separated for trial.

- Plaintiff will be permitted to present evidence to support its claims of understaffing and inadequate policies with regard to what Defendant could and should have done if it had adhered to the applicable standard of care governing the nursing home industry.

- Evidence about the operation of Defendant’s facilities other than the Lebanon facility during periods of time other than the year when Decedent resided at Defendant’s facility and passed away generally will not be permitted.

L.C.C.C.P. No. 2017-01517, Opinion by Bradford H. Charles, Judge, April 29, 2020.

IN THE COURT OF COMMON PLEAS OF LEBANON COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA

CIVIL ACTION – LAW

JASON R. ULSHAFER, Executor : No. 2017-01517

for the estate of :

WILLIAM J. ZIMMERMAN, Deceased :

Plaintiff :

:

- :

:

:

HCR MANORCARE, INC. ET AL, et al :

Defendants :

ORDER OF COURT

AND NOW, this 29th day of April, 2020, upon consideration of the Defendant’s Pre-Trial Motions and in accordance with the attached Opinion, the Order of this Court is as follows:

- All decisions that implicate an analysis of probative value and prejudicial effect under Pa.R.Ev.403 will be deferred until the time of trial.

- The Defendants’ Motion seeking to preclude testimony of Dr. Zyad Mirza based upon principle of Frye v. United States, 293 F.1013 (D.C.Cir. 1923) is DENIED.

- The Defendants’ request to preclude the Plaintiff from using the words “abuse” and “neglect” is DENIED.

- The Defendants’ Motion seeking to preclude Plaintiff from using exhibits that were vaguely and insufficiently described is GRANTED in accordance with the attached Opinion.

- The Defendants’ Motion seeking to preclude evidence of the Defendants’ bonus program is DEFERRED until trial in accordance with the attached Opinion. No mention of the bonus plan will be made to the jury until a sidebar conference has occurred to address the issue.

- The Defendants’ Motion seeking to preclude the introduction of Defendants’ cost reports is DEFERRED until trial in accordance with the attached Opinion.

- The Defendants’ Motion seeking to preclude the introduction of resident council meeting notes is DEFERRED until trial in accordance with the attached Opinion.

- The Defendants’ Motion to prevent introduction of Pennsylvania Department of Health survey results is DEFERRED until trial. No mention of the survey results will be made to the jury until a sidebar conference has occurred to address the issue.

- The Defendants’ Motion seeking to preclude evidence of understaffing and under-budgeting is DENIED.

- The Defendants’ Motion seeking to preclude Nurse Jessica Petka from rendering an opinion regarding causation is GRANTED in accordance with the attached Opinion.

- The Defendants’ Motion seeking to preclude anyone, including Dr. Ziad Mirza from arguing an opinion that Plaintiff suffered harm as a result of Defendants’ understaffing is DENIED.

- The Defendants’ Motion seeking to preclude testimony from Defendants’ corporate executives is DEFERRED until trial in accordance with the attached Opinion.

- The Defendants’ Motion in Limine seeking to preclude testimony from Anna Haulman is DENIED.

- The Defendants’ Motion in Limine challenging authenticity of a photograph purportedly depicting the wound of William J. Zimmerman is DEFERRED until trial.

- The Defendants’ Motion to trifurcate trial is DENIED. However, trial will be bifurcated in accordance with the attached Opinion.

- A telephone conference with counsel to discuss the timing of trial will be conducted on June 30, 2020 at 8:30am. Counsel are to provide telephone numbers where they can be reached to the Judicial Assistant of the undersigned at least two (2) days in advance of the telephone conference. One hour has been set aside for this conference. Counsel are directed to have their calendars available for the months of November 2020, December 2020, January 2021, and February 2021. Our goal at the telephone conference will be to establish a date certain for the above-referenced trial.

BY THE COURT:

BRADFORD H. CHARLES, J.

BHC/pmd

Cc: Court Administration (order only)

William Mundy, Esq., John Skrocki, Esq.// 100 Four Falls, Suite 515, 1001 Conshohocken State Rd. West Conshohocken PA 19427

Ryan J. Duty, Esq.// 437 Grant St, Suite 912, Pittsburgh PA 15219

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Preamble 1

- Facts & Procedural Background 2-5

- Discussion 5-48

- Relevance and Scope of Trial 6-8

- Probative Value v. Prejudicial Effect 8-10

- MANORCARE’s Frye Motion 11-13

- Motions in Limine 14-45

- Preclusion of words “abuse” & “neglect” 14-15

- Use of Exhibits 16-17

- Bonus Program 18-19

- Cost Reports 19-21

- Resident Council Meeting Minutes 21-23

- Department of Health Surveys 23-31

- Understaffing 31-33

- Nurse Petka’s Opinion 34-40

- Opinion as to Causation 40-42

10 Testimony of Corporate Managers 42-43

11 Testimony of Former Employee 44-45

12 Authenticity of Photograph 45

- Motion to Trifurcate Trial 46-48

- Conclusion 48-49

IN THE COURT OF COMMON PLEAS OF LEBANON COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA

CIVIL ACTION – LAW

JASON R. ULSHAFER, Executor : No. 2017-01517

for the estate of :

WILLIAM J. ZIMMERMAN, Deceased :

Plaintiff :

:

- :

:

:

HCR MANORCARE, INC. ET AL, et al :

Defendants :

APPEARANCES:

Ryan Duty, Esq. FOR PLAINTIFFS

William Mundy, Esq. and John Skrocki, Esq. FOR DEFENDANTS

Opinion, Charles, J., April 29, 2020

The above-referenced case was scheduled for trial during the April 2020 term of Court. It was postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic. However, before the postponement became necessary, the Defendant filed thirteen (13) different pre-trial motions seeking to essentially gut the Plaintiff’s case. Although a few of the Defendants’ arguments have resonated with this Court, most of the Defendants’ motions will be either denied or deferred until trial. We issue this Opinion to briefly address each of the Defendants’ pending motions.

- FACTS AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND

In 2016, 89-year old William J. Zimmerman (hereafter ZIMMERMAN) spent about one (1) month as a resident of the Defendants’ nursing home facility in Lebanon. (All of the Defendants will hereafter be referenced as MANORCARE). Prior to his admission into the MANORCARE facility, ZIMMERMAN had been a patient at the Gnadden-Huetten Hospital as a result of chronic severe right knee pain. ZIMMERMAN had been diagnosed with cellulitis and monoarthritis. In addition, ZIMMERMAN had a long and complex medical history that included obesity, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea and numerous muscular-skeletal issues.

On January 31, 2016, while a resident at MANORCARE, ZIMMERMAN complained of pain and tenderness in his right foot. He was noted to have a blister on his left foot. Wound care was performed on February 11, 2016 and an arterial Doppler study was undertaken.

On February 12, 2016, ZIMMERMAN was seen by a vascular surgeon at the Hershey Medical Center. Diagnostic tests ruled out osteomyelitis but revealed degenerative changes consistent with gout and arthritis.

Unfortunately, ZIMMERMAN’s condition did not improve. He underwent a left leg amputation below the knee on February 23, 2016. Following the amputation, ZIMMERMAN was returned to the Gnadden-Huetten Hospital. He was discharged to his home on March 14, 2016, and placed on hospice services. He eventually died on July 1, 2016.

ZIMMERMAN’s estate filed a civil complaint on September 27, 2017. Numerous theories of liability were proposed in the complaint. However the gravamen was that MANORCARE neglected to promptly diagnose and address ZIMMERMAN’s foot wound. According to PLAINTIFF, the MANORCARE facility in Lebanon was chronically understaffed and lacked resources necessary to properly monitor and provide care for its residents. PLAINTIFF alleges that the amputation of ZIMMERMAN’s leg could have been prevented had MONORCARE promptly diagnosed and treated his foot wound.

Following discovery, MANORCARE filed a Motion for Summary Judgment. Via a Court Order we entered on September 27, 2019, we dismissed the PLAINTIFF’s non-negligence related claims. We stated:

“To the extent that PLAINTIFF seeks to transform this case into something more than a simple negligence dispute, and to the extent that PLAINTIFF seeks to impose upon MANORCARE an enhanced duty that transcends reasonable care, we reject the PLAINTIFF’s efforts. Via the procedural vehicle afforded by MANORCARE’s Motion for Summary Judgment, we advise both parties that this case will be tried as a negligence case and, potentially, as one for punitive damages if and only if a jury determines that MANORCARE’s conduct exceeded the threshold necessary for such damages to be awarded.” (Slip Opinion at page 22)

We conducted a Pre-Trial Conference in the above-referenced matter on March 12, 2020. During the Pre-Trial Conference, MANORCARE’s counsel indicated that it would be proffering a so-called “Frye Motion” to challenge the science underlying PLAINTIFF’s expert opinion. In addition, MANORCARE’s counsel also indicated that he would be filing “several” Motions in Limine seeking evidentiary rulings prior to trial. We established deadlines for the filing of these Pre-Trial Motions. MANORCARE complied with the deadlines. On or about April 1, 2020, this Court received a box with eleven (11) motions. Because one of the motions implicated several issues, and because MANORCARE’s “Frye Motion” was filed separately, there are now thirteen (13) separate issues that must be resolved by this Court. Those issues are:

- A Frye Motion to restrict testimony of Doctor Mirza regarding causation;

- A Motion in Limine seeking to preclude PLAINTIFF from using the terms “abuse” and “neglect”;

- A Motion in Limine seeking to preclude PLAINTIFF’s use of certain exhibits;

- A Motion in Limine seeking to preclude evidence of MANORCARE’s bonus program;

- A Motion in LImine seeking to preclude admissibility of cost reports;

- A Motion in Limine seeking to preclude introduction of resident council meeting notes;

- A Motion in Limine to prevent introduction of Department of Health surveys;

- A Motion in Limine to preclude evidence of understaffing and underbudgeting;

- A Motion in Limine to preclude Nurse Petka from rendering an opinion regarding causation;

- A Motion in Limine to preclude testimony from corporate managers of MANORCARE;

- A Motion in Limine to preclude “irrelevant former employee testimony”;

- A Motion in Limine challenging the authenticity of a photograph of ZIMMERMAN’s wound;

- A Motion to trifurcate trial.

- DISCUSSION

There are two concepts that permeate all of MANORCARE’s various motions. The first involves relevance of evidence, which will necessarily govern the scope of the trial. The second theme of MANORCARE’s pre-trial filings is related to the first. It involves an analysis under Pa.R.Ev.403 that requires the Court to weigh probative value versus prejudicial effect. To avoid duplication of analysis, we will set forth our comments regarding relevance/scope of trial and probative value versus prejudicial effect first. Thereafter, we will separately analyze MANORCARE’s Frye motion and all of its Motions in Limine. We will end by addressing MANORCARE’s Motion for trifurcation.

- Relevance/Scope of Trial

From reading the parties’ submissions, it is obvious that each has a different perspective about what is relevant to a fair determination. PLAINTIFF proposes an extremely broad scope that would enable a jury to assess all aspects of how MANORCARE operated its nursing care facilities. MANORCARE believes that the focus of the trial should be limited to what it did or did not do with respect to ZIMMERMAN. Not surprisingly, this Court believes that fairness requires that we define relevance somewhere between the polarized perspectives of both parties.

The role of this jury will be to determine whether MANORCARE was negligent in its care of ZIMMERMAN. Of necessity, this will require the jury to evaluate how MANORCARE provided care for persons situated similarly to ZIMMERMAN. The policies and procedures regarding care of wounds, infection control and the frequency of physical evaluations and inspections will all be relevant areas of concern given the factual scenario that this case presents. If in fact MANORCARE could not adequately inspect and care for wounds and/or infections because its policies were inadequate or because it was understaffed, then to that extent the staffing and policy concerns proffered by PLAINTIFF could be relevant.

With the above being said, our analysis of relevance stops well short of the “almost anything goes” approach proffered by the PLAINTIFF. We are more than skeptical about how MANORCARE’s operations of facilities other than Lebanon could somehow help this jury determine the above-referenced dispute. Similarly, allegations about deficiencies in terms of food service, painting of restrooms, or patient falls that occurred in the Lebanon facility would only be of limited assistance to a jury’s determination of whether MANORCARE should have treated ZIMMERMAN’s wounds in a different fashion.

At this point, we have a broad understanding of the above-referenced case, but we are not arrogant enough to believe that we have the insight that is possessed by counsel following hundreds of hours of depositions and document review. Because of this, we are reluctant to render any final decisions regarding relevance in advance of trial. With this being said, we do wish to impart the following to both parties:

- The primary focus of this trial must be upon the care provided or not provided by MANORCARE to ZIMMERMAN.

- The above focus implicates not only what MANORCARE did do with respect to ZIMMERMAN, but also what MANORCARE could and should have done had it adhered to the applicable standard of care governing the nursing home industry. Within the rubric of “what should have been done”, we will permit PLAINTIFF to present evidence to support its claims of understaffing and inadequate policies.

- We cannot imagine any circumstance under which we would permit evidence about the operation of MANORCARE’s facilities other than the one in Lebanon during periods of time other than 2016. This case is not an indictment of MANORCARE as a corporate entity; it is a challenge to how MANORCARE provided care for one particular patient during early 2016.

In our Opinion regarding MANORCARE’s Motion for Summary Judgment, we stated: “At its core, this is a dispute about nursing home negligence.” We also stated: “To the extent that PLAINTIFF seeks to transform this case into something more than a simple negligence dispute, and to the extent that PLAINTIFF seeks to impose upon MANORCARE an enhanced duty that transcends reasonable care, we reject the PLAINTIFF’s efforts.” To those proclamations, we add this – the negligence alleged pertains to care provided, or not provided, to ZIMMERMAN. All decisions regarding relevance will be viewed through this prism.

- Probative Value versus Prejudicial Effect

Pa.R.Ev. 403 states: “The Court may exclude relevant evidence if its probative value is outweighed by…unfair prejudice, [confusion], undue delay…or needlessly presenting cumulative evidence.” In almost everyone one of its Motions in Limine, MANORCARE argues that the prejudicial effect of the challenged evidence outweighs its probative value. Thus, MANORCARE asks that the evidence be excluded under Pa.R.Ev. 403.

Evidence will not be prohibited as unduly prejudicial merely because it is harmful to a party. See, e.g. Leahy v. McClain, 732 A.2d 619 (Pa. Super. 1999). “Unfair prejudice supporting exclusion of relevant evidence means a tendency to suggest a decision on an improper basis or divert the jury’s attention away from its duty of weighing the evidence impartially.” Parr v. Ford Motor Company, 109 A.3d 682,696 (Pa. Super. 2014). Citing Commonwealth v. Wright, 961 A.2d 119 (Pa. 2008) “The law ‘does not require a court to sanitize a trial to eliminate all unpleasant facts from the jury’s consideration where those facts are relevant to the issues at hand…” Smith v. Morrison, 47 A.3d 131, 137 (Pa. Super. 2012). Citing Commonwealth v. Page, 965 A.2d 1212 (Pa. Super. 2009).

As is obvious from the above, a “probative value versus prejudicial effect” analysis requires a court to analyze the totality of evidence presented. At this point, this Court has not heard the testimony of one single witness, nor do we pretend to have prescient knowledge about how this trial will unfold. Stated simply, we lack insight at this point to fairly undertake a “probative value versus prejudicial effect” analysis.

The United States Supreme Court has declared that a “prejudicial effect versus probative value” analysis “requires a fact-intensive, context-specific inquiry.” Sprint/United Management Company v. Mendelsohn, 552 U.S. 379, 128 S.Ct. 1140 170 L.Ed. 2d 1 (2008). Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court has declared: “Since the pre-trial record will almost necessarily be inadequate for making a decision based upon an as-yet unknown trial tableau,…Rule 403 is a “trial-oriented rule.” Commonwealth v. Hicks, 91 A.3d 47, 53 (Pa. 2014). Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court expounded on this opinion by stating:

“Here, the trial court excluded proffered testimony pre-trial pursuant to Rule 403, a rule that, as explained infra, is generally not susceptible to accurate pre-trial evaluation. Unlike other rules of evidence, Rule 403 requires a trial court to weigh probative value and prejudice – the cost and benefits of relevant evidence – viewing it as part of a whole and not in isolation. Inherent in the rule is the assumption that the Court has an adequate record, one that will mirror or provide great insight into what will develop at trial. In the majority of cases, and particularly manifested in this one, the trial court has no way of knowing beforehand exactly what evidence will be presented at trial. Depending upon the case and the inevitable vagaries of litigation, the pre-trial record may be entirely different than the record that eventuates as matters unfold. Even if the evidence the parties intend to present is set, a trial rarely follows the anticipated script. The actual value of evidence may differ substantially from pre-trial expectations, depending on all manner of factors, such as the availability, appearance, memory, or demeanor of a witness, admissions on cross-examination, the defense theory, or the defendant’s decision whether or not to testify. Even a relatively developed pre-trial record will be of limited utility in prediction the probative value or prejudice a particular piece of evidence will ultimately have.”

Id at page 52-53.

Given our limited insight into what will occur at trial, and based upon Hicks, we will not adjudicate any of the Defendant’s Rule 403 objections in advance of trial. Although we will discuss relevance within this Opinion, we will not balance relevant information against prejudicial effect until the time of trial. Effectively, we decline today to rule on any Rule 403 objection in favor of deferring such a decision until the time of trial.

- MANORCARE’s Frye Motion

In any case involving scientific evidence, the Court is charged with the responsibility to serve as a ‘gatekeeper” in order to insure that “junk science” does not find its way into a courtroom. Although Federal Courts have examined the efficacy of scientific evidence based upon a standard that was enunciated in 1993 in the case of Daubert v. Merrill Dow Pharmaceuticals, 509 U.S. 579 (1993), Pennsylvania has chosen to adhere to an earlier test that was first announced in the case of Frye v. United States, 293 F. 1013 (D.C. Cir. 1923). In Frye, the Court concluded that scientific evidence should only be accepted in a courtroom where the proffered scientific methodology had “gained general acceptance in the particular field in which it belongs.” Stated differently, the Frye test requires that the methodology employed to render an opinion in court must be “generally accepted” among the scientific community. See, Frye, supra; Commonwealth v. Topa, 369 a.2d 1277 (Pa. 1977).

Frye cannot be used a vehicle to challenge an opinion with which a party disagrees. Therefore, Frye does not apply every time science enters a courtroom. See, Trach v. Fellin, 817 A.2d 1102 (Pa. Super. 2003). See also, Pa.R.Ev. 702. A Frye challenge focuses upon methodology and not ultimate conclusion.

In this case, MANORCARE challenges the testimony that PLAINTIFF wishes to elicit through Dr. Zaid Mirza. Dr. Mirza is a board certified physician who has over thirty (30) years’ experience practicing medicine. He is a founding member of the Wound Healing Centers of America located in Towson, Maryland, he has served as Medical Director at several nursing home facilities, and he has presented or authored publications regarding care of wounds within a nursing home environment.[1] In his written report, Dr. Mirza concluded that MANORCARE’s services “failed to adhere to the applicable standards of care in their care and treatment of Mr. Zimmerman”, that MANORCARE’s parent companies failed to provide proper oversight to the Lebanon facility, and that the Lebanon facility’s breach of care caused “an infected wound and osteomyelitis and loss of limb, leading to further physical and mental decompensation and eventual death.”[2]

It is the Dr. Mirza’s opinion regarding causation that MANORCARE challenges under Frye. According to MANORCARE, Dr. Mirza’s conclusions about causation are vague and factually unsupported.

We do not view MANORCARE’s challenge of Dr. Mirza to be governed by Frye. The Frye test was developed to prevent expert testimony based upon fraudulent scientific principles; it was not designed to prevent experts from rendering opinions that may have sub-optimal factual support. Under the latter circumstance, juries serve as the arbiter or what is or is not acceptable. See, e.g. Miller v. Brass Rail Tavern, 664 A.2d 525 (Pa. 1995).

Dr. Mirza has a lifetime of experience dealing with wound care in the context of a nursing home environment. We presume that he has experience dealing with hundreds if not thousands of elderly patients who experienced wounds similar to the one suffered by ZIMMERMAN. Of necessity, Dr. Mirza will have gained insight from that lifetime of experience into how elderly wounds should be treated. Without question, he will also be familiar with the consequences of failing to properly treat wounds.

We are well aware that ZIMMERMAN was 89 years old. We are well aware that ZIMMERMAN suffered from a plethora of pre-existing problems that were not caused by MANORCARE. We are well aware that ZIMMERMAN was a resident of MANORCARE for only about a month. We are well aware the there are differing medical opinions in this case regarding the nature and extent of ZIMMERMAN’s wound. We are also well aware that there are qualified physicians who have and will disagree with Dr. Mirza’s opinion that ZIMMERMAN’s wound ultimately lead to his leg amputation and death. Our awareness of all of the above does not justify a de facto dismissal of PLAINTIFF’s case that would result from preclusion of PLAINTIFF’s chief expert based upon Frye. Ultimately, all of the facts of this case will have to be weighed by a jury. We will not effectively take this case away from a jury by ruling that PLAINTIFF’s primary expert has somehow run afoul of the Frye test. We will therefore deny MANORCARE’s Frye Motion.

- Motions in Limine

MANORCARE has filed eleven (11) separate Motions in Limine. Because one of the motions included several components, we have broken out MANORCARE’s Motions in Limine into twelve (12) separate requests for relief. With our preliminary comments regarding relevance in mind, our analysis with respect to each of the Motions in Limine will be set forth below seriatim.

- Preclusion of words “abuse” and “neglect”

MANORCARE requests a Court Order seeking to preclude PLAINTIFF, his witnesses and/or his counsel from using the words “abuse” or “neglect”. MANORCARE characterizes such words as “inflammatory” and argues that “they exist solely to inflame and anger the fact-finder by implying that Defendants engaged in abhorrent or even criminal behavior which lead to Mr. Zimmerman being injured.” (See, Paragraph 17-18 of MANORCARE’s motion).

Without question, the words “abuse” and “neglect” can be provocative, but they are also descriptive. In fact, both terms are defined by Federal regulations that govern long-term care facilities. For example, “abuse” is defined as including “the deprivation by an individual, including a caretaker, of goods or services that are necessary to attain or maintain physical, mental, and psychosocial well-being.” Similarly, the word “neglect” is defined as “the failure of the facility, its employees or service providers, to provide goods and services to a resident that are necessary to avoid physical harm, pain, mental anguish, or emotional distress.” See, 42 C.F.R. § 488.301.

It is not good practice for a Court to supplant a party’s rhetoric with its own. Generally speaking, each witness and each lawyer should be free to employ oratory, diction and jargon that he/she believes will advance a cause. There are, of course, some limits upon counsel’s choice of speech[3], but those limits are few and far between. As a rule, lawyers should be given free rein to use what our Superior Court has described as “oratory flare” in pursuing a client’s cause.

We will not prohibit PLAINTIFF, his witnesses, or his experts from using words such as “abuse” and “neglect”. Neither will we prevent MANORCARE’s counsel from using words such as “greedy” and “opportunistic” to describe the PLAINTIFF. All such words are provocative, but they are also descriptive and we will not artificially micromanage the language that either counsel wishes to employ. With this being said, we voice a word of caution to counsel. In the experience of this Court, parties who overreach by using hyperbolic language will almost always pay a price in the eyes of Lebanon County juries. With that caution being expressed, MANORCARE’s Motion in Limine seeking to preclude use of “abuse” and “neglect” will be denied.

- Use of Exhibits

MANORCARE objects to the use of Exhibits 35, 36, 39, 40, 41, 47, 48, 50, 51 and 52 set forth in PLAINTIFF’s Pre-Trial Statement. Those exhibits were described in PLAINTIFF’s Pre-Trial Memorandum as follows:

35 – Any deposition transcript with exhibits…

36 – Any exhibits to any deposition taken in this matter or any other matter involving these same Defendants…

39 – Any and all documents which Defendants have been requested to produce but have not yet produced in discovery…

40 – Any and all affidavits attesting to loss, missing or destroyed documents…

41 – All correspondence, pleadings, discovery requests and responses and Court Orders filed in this matter…

47 – Any exhibits which at this time may be unknown but may subsequently become known…

48 – All documents or any other matters that have been produced or will be produced…in this matter or any other matter involving these same Defendants…

50 – The complaint in any other filing from the lawsuit entitled United States ex rel Rihik v. Manorcare Inc….

51 – The complaint and any other filing from the lawsuit styled United States ex rel Slough v. HCR Manorcare…

52 – The complaint and any other filing in the lawsuit styled United States ex rel Carson v. HCR Manorcare… .

Without question, all of the above designated exhibits are imprecisely described. More alarming, the breadth of the exhibit description is stunningly broad and could encompass literally tens of thousands of documents that may or may not ever have been seen by MANORCARE’s counsel in this lawsuit. We will not permit such an overly broad designation of exhibits. PLAINTIFF will therefore be precluded from introducing in its case in chief any document sought to be admitted exclusively under the rubric of Exhibits 35, 36, 39, 40, 41, 47, 48, 50, 51 and 52.

We stop short of preventing all use of any such documentation during trial. For example, if MANORCARE’s expert proffers an opinion that diametrically contradicts an opinion rendered in a previous case, PLAINTIFF’s counsel should not be prevented from confronting the expert with the prior contradictory documentation. With that being said, using the guise of impeachment to present a plethora of questionably relevant documentation generated by or about other cases is not a practice that we will view favorably. Before any such documentation is used, counsel will be required to approach the Bench in order to specifically address the questions of “what” and ”why” outside the presence of the jury. For now, we will grant MANORCARE’s objection to the use of Exhibits 35, 36, 39, 40, 41, 47, 48, 50, 51 and 52 within PLAINTIFF’s case in chief.

- Bonus Program

For a couple of minutes during a deposition that lasted two (2) hours, MANORCARE’s Lebanon Administrator George Frill described a bonus program that applied to him. (See, N.T. 79-82). None of the expert reports that were attached to MANORCARE’s Motions mention this bonus plan, nor were we presented with any information to even quantify how much money Mr. Frill did or could have received pursuant to this plan during 2016. MANORCARE asserts that the bonus plan described by Mr. Frill is not relevant to this dispute and evidence of such a plan should be precluded at the time of trial.

PLAINTIFF responds by claiming that the mere existence of a bonus program establishes the type of corporate control that is relevant to the issue of corporate negligence. In his brief, PLAINTIFF states:

“The bonus information demonstrates that the corporate defendants’ exercise control over the daily operations of the facility; and, in turn, negatively impacted the quality of care that residents such as Mr. Zimmerman received. The bonus program/criteria support Plaintiff’s allegations by showing that defendants utilized bonus parameters to promote and incentivize the systemic understaffing of Defendants’ facility during the relevant time period. The bonus program reveals that Defendants administrative and supervisory employees received bonuses in exchange for increasing the number of high-acuity Medicare residents while simultaneously keeping staff numbers low, thereby compromising the quality of care rendered to all residents.” (Plaintiff’s brief at pages 6-7).

We will defer a final decision regarding relevance of Mr. Frill’s bonus program until the time of trial. However, we warn PLAINTIFF’s counsel that no mention of this bonus program should be undertaken until or unless specific permission is obtained from the Court after a sidebar conference. An offer of proof far more detailed than Mr. Frill’s deposition testimony will have to be presented in order for us to permit a jury to hear about the bonus program. Specifically, something on the magnitude of “Frill’s compensation is predicated upon keeping down costs of wound care” will be required before we should permit such testimony.

For today, we will defer a decision regarding admissibility of the bonus program. A final decision will be rendered at trial after sidebar deliberation with counsel.

- Cost Reports

During discovery, MANORCARE produced documents pertaining to the cost of operating its Lebanon facility. Administrator George Frill provided testimony in his deposition regarding that documentation. (N.T. 50-56). However, no accountant or financial expert evaluated MANORCARE’s cost reports or linked them specifically to ZIMMERMAN’s care. Because of this, MANORCARE argues: “The raw numbers alone, without analysis, or context, serve only to confuse, mislead and potentially incite the passions of the fact-finder.” (MANORCARE’s Motion at Paragraph 18).

PLAINTIFF responds by citing its “central theory” that MANORCARE elevated its own profits over caring form residents. Without any reference to the record, PLAINTIFF proffers the bold statement that MANORCARE shifted income from its Lebanon facility to “related entities”, thereby reducing money available for staffing and supplies. (Plaintiff’s brief at page 8). In addition, PLAINTIFF argues that the cost reports emphasize the degree of corporate control exercised by MANORCARE over its Lebanon facility. PLAINTIFF argues that this degree of control is relevant with respect to the issue of corporate negligence.

Initially, we reject MANORCARE’s objection to cost reports based upon hearsay. Under Pennsylvania law, records of activity conducted in the regular course of business are admissible under the so-called “business records” exception to hearsay. See, Pa.R.Ev. 803(6). By definition, MANORCARE’s cost reports fall within this category.

More difficult is the issue of relevance. We are bothered by the fact that no link has been drawn by any expert between MANORCARE’s cost reports and the care provided to ZIMMERMAN. On the other hand, allocation of resources is always relevant in a claim of nursing home negligence. We question how PLAINTIFF will be able to prove through cost reports that MANORCARE inappropriately allocated resources to the detriment of ZIMMERMAN. Unfortunately, PLAINTIFF’s brief did not afford much education on this point.

As we noted at the outset of this Opinion, we will not permit this case to become a general indictment on how MANORCARE operated its nursing home facilities, including the one in Lebanon. To the extent that PLAINTIFF wishes to challenge MANORCARE’s corporate budget and accounting policies, this case will not be the vehicle to do that.

With the above being said, we will not preclude PLAINTIFF from pursuing its “profits over patients” theory. To the extent that PLAINTIFF can draw a link between ZIMMERMAN’s alleged deterioration and inability of MANORCARE to discover and/or treat that condition, we believe that PLAINTIFF should be able to do that. Ultimately, whether MANORCARE’s cost reports will be shown to the jury or not will be determined using a probative value versus prejudicial effect analysis under Pa.R.Ev. 403. We will allow MANORCARE to have the opportunity to pursue its profits over patients argument.[4]

- Resident Council Meeting Minutes

Apparently, MANORCARE’s Lebanon facility maintained a resident council that served as an intermediary between the facility administration and residents. Each resident council meeting was memorialized by minutes. According to MANORCARE, the minutes represent “inadmissible hearsay” that is not relevant to any issue now in dispute.

All of the resident council meeting minutes were appended to MANORCARE’s motion. We read each one. It quickly became abundantly clear that most of the time expended in resident council meetings involved food service. That being said, we did located some meeting notes that involved staffing:

- 8-27-15 – “Request for more staff” noted;

- 10-29-15 – “Praise for staff efforts. Want more staff.”;

- 11-19-15 – Addition of new staff noted;

- 1-28-16 – Call bell response too slow “on rehab”;

- 3-31-16 – “Staffing issues ongoing” noted directly before the phrase “dining room staffing”.

We consider the resident council meeting minutes to be “business records” of MANORCARE. Those minutes are maintained in the regular course of MANORCARE’s business. The minutes are obviously designed to provide data that MANORCARE can use to operate its facility. Given the above, we conclude that the meeting minutes fall within the so-called “business records exception” to the hearsay rule. (See, Pa.R.Ev. 803(6)). Thus, MANORCARE’s hearsay objection will be overruled.

More troubling is MANORCARE’s objection regarding relevance. Without testimonial amplification, the words contained in the meeting minutes do not add much, if anything, to this dispute. While some of the minutes reflect a request for “more staff”, it is not clear whether the additional staff was sought for food service, entertainment or in-room wound evaluation. The one note that seemed to be emphasized by PLAINTIFF’s experts was that a “call bell response” was “too slow on rehab”. We do not even know what this means.

We cannot foreclose the possibility that testimony will be available to amplify the nature of the complaints and requests submitted by or to the resident council. However, we warn PLAINTIFF that such testimonial amplification will be needed because the meeting minutes, by themselves, do not provide proof that MANORCARE’s wound care services were inhibited by staffing or budgetary constraints.

We will defer a final decision regarding admissibility of the resident council meeting minutes until the time of trial. When those minutes are offered in evidence, we will consider all testimony in evidence that was presented to corroborate relevance of the words contained in the minutes themselves.

- Department of Health Surveys

The Pennsylvania Department of Health inspects nursing homes on an annual basis. The results of these week-long inspections are set forth in written reports called “Surveys”. When a facility fails to adhere to standards maintained by the Department of Health, they are issued a “Survey Deficiency”. MANORCARE’s Lebanon facility was inspected in January of 2016. The survey report issued by the Department of Health determined that MANORCARE Lebanon “was not in compliance” with health code regulations. Four (4) “deficiencies” were identified. One involved problems with painting in a restroom. The second implicated the need for MANORCARE to take additional steps to prevent patients from falling. The third deficiency alleged that MANORCARE provided “unnecessary” medications to a patient. The fourth and final deficiency alleged that MANORCARE failed to establish and maintain an appropriate infection control program. Only the fourth of these deficiencies is even conceivably related to this dispute.

MANORCARE objects to the Department of Health survey results. MANORCARE alleges that the reports are hearsay in that they represent little more than opinions of an inspector who will not be subject to cross-examination. In addition, MANORCARE alleges that the survey reports are not relevant to the dispute now before the Court.

Generally speaking, out of court statements by a non-testifying witness are considered inadmissible hearsay. Pa.R.Ev. 802. However, our General Assembly has created an “official records” exception to the hearsay rule. Section 6104(b) of the Judicial Code states:

“A copy of a record authenticated as provided in §6103 disclosing the existence or non-existence of facts which have been recorded pursuant to an official duty or would have been so recorded had the facts existed shall be admissible of evidence of the existence or non-existence of such facts, unless the sources of information or other circumstances indicate a lack of trustworthiness.

42 Pa.C.S.A. §6104(b).

This statute is consistent with Pennsylvania Common Law principles. See, e.g. Ledford v. Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad Company, 345 A.2d 218 (Pa. Super. 1975) (Inspection report admitted as a business record exception to hearsay) and In re Estate of Jones, 136 A.2d 327 (Pa. 1957) (Commonwealth’s tax appraisal admissible as a public record).

The Department of Health nursing home survey reports are official records as that term is defined in 42 Pa. C.S.A. §6104. As such, facts contained within these reports are admissible. We therefore conclude that admissibility of the Department of Health survey reports are not barred by rules governing hearsay.

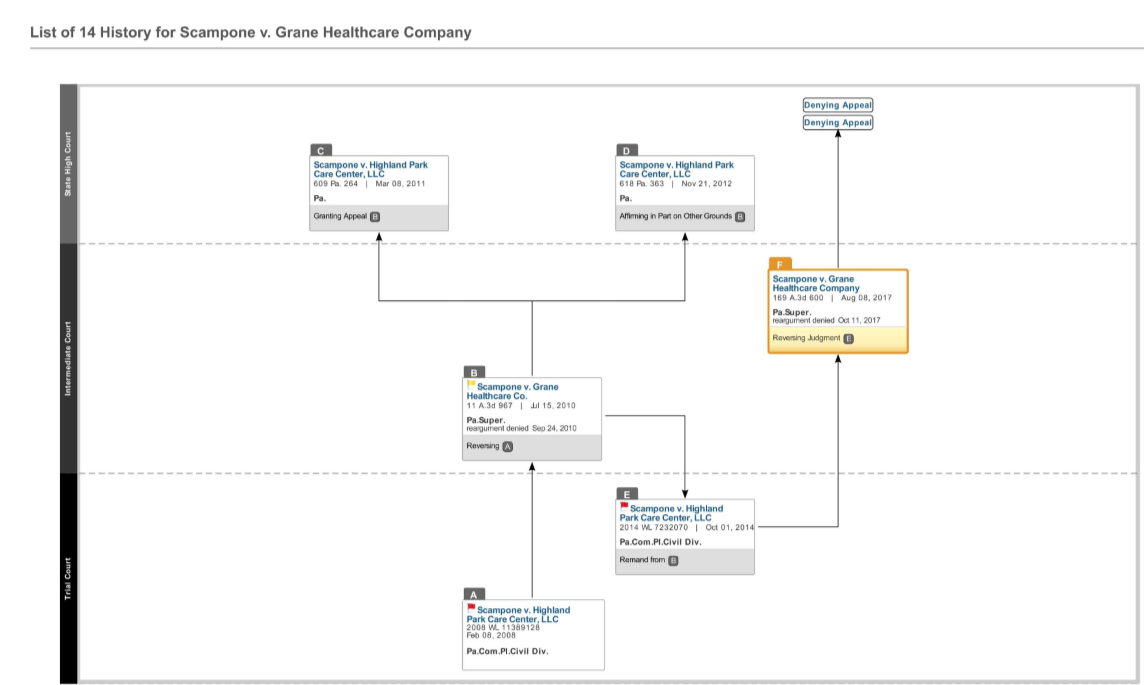

More difficult is the question of relevance. As noted above, PLAINTIFF takes an expansive view of what should or should not be relevant. Relying upon Scampone v. Grane Healthcare Company, 169 A.3d 600 (Pa. Super. 2017), PLAINTIFF argues that the existence of “across-the-board substandard care” was relevant to show that MANORCARE was incapable of complying standard of care. MANORCARE disagrees with PLAINTIFF’s expansive view of survey deficiencies. MANORCARE argues that none of the deficiencies were relevant to wound care; none should therefore be admitted in evidence.

The case of Scampone v. Grane Healthcare Company has a lengthy and somewhat tortured history. Attached is a chart found in Westlaw that highlights that procedural history.[5] According to PLAINTIFF, the decision most germane to the issue now before us is the one rendered by the Superior Court in 2017. We agree.

The Superior Court’s 2017 Opinion in Scampone focuses on a number of rulings rendered by the Allegheny Court of Common Pleas in a nursing home liability dispute. One of the issues addressed by the Superior Court involved Department of Health surveys. According to the Opinion, the trial judge admitted evidence of survey deficiencies that directly implicated the care – or lack thereof – that allegedly caused the Plaintiff’s harm. However, the judge refused to admit evidence of survey deficiencies unrelated to the issue before the jury. Within the context of a discussion about punitive damages, Pennsylvania’s Superior Court stated that all of the survey results should have been presented to the jury:

“Herein, the trial court prohibited Mr. Scampone from introducing into evidence certain Pennsylvania Department of Health (“DOH”) surveys. The trial court admitted into evidence DOH surveys related to the failure to hydrate patients properly, which was the condition that lead to Madeline’s death, but refused to admit DOH surveys that pertained to other substandard patient-care issues found by the DOH at the nursing home.

Mr. Scampone argues that all DOH deficiencies outlined in surveys from August 22, 2002 through July 16, 2004, regarding patient care at the nursing home, were admissible to demonstrate that the Defendants were aware of various dangerous conditions that existed at the nursing home and that they recklessly disregarded their responsibility to correct them. The excluded surveys established that, in the years preceding Madeline’s death, Highland/Grane violated DOH regulations by, inter alia, neglecting to: (1) develop comprehensive resident care plans for each resident; (2) comply with numerous physician orders regarding patient care for residents, including orders for laboratory tests; (3) promptly notify the DOH of a serious incident; (4) notify physicians of significant changes in residents’ condition; (5) meet a number of residents’ physical and nutritional needs; and (6) establish an infection control program.

We concur that surveys were relevant to the issue of punitive damages…the surveys demonstrated the existence of across-the-board substandard care rendered at the nursing home and were relevant to show that Highland and Grane had knowledge of these deficiencies in patient care and blithely ignored them by failing to increase staffing levels. The surveys, Mr. Scampone continues, notified Highland/Grane that there were numerous issues regarding the quality of patient care at the facility and proved that, despite this knowledge, Highland/Grane knowingly failed to take corrective measures to remedy the neglect of patients at the facility. In other words, the deficiencies involved with Madeline’s care were not isolated incidents, and the DOH surveys demonstrated that the nursing home was operated in a systemic manner such that patient neglect was common.

The surveys in question demonstrated various issues of consequence regarding patient care at the nursing home. The failure to respond appropriately to these findings tended to establish that the Defendants acted with reckless disregard as to the safety of their patients….

In this case, there was proof of systemic understaffing, the Defendants’ knowledge of the same and inaction in the face of it, and the Defendants’ employees altered patient records to reflect that care was given when it was not. The DOH surveys had a tendency to confirm that these types of abuses occurred. They were therefore relevant, and the trial court abused its discretion in excluding then from evidence.”

Id at pages 626-627.

In this case, there are four deficiencies at issue. One involved the quality of painting in a restroom. This deficiency clearly did not implicate patient care. None of PLAINTIFF’s experts reference the painting deficiency as related in any way to ZIMMERMAN. We therefore conclude that the survey deficiency pertaining to restroom painting is totally irrelevant to any issue that the jury will have to decide. We will grant MANORCARE’s motion to exclude such evidence.

All of the three other deficiencies implicate patient care. However, the deficiencies involving patient falls and providing unnecessary medication do not directly relate to the situation involving ZIMMERMAN. Nowhere in the record presented to us is there any evidence that ZIMMERMAN suffered a fall while at MANORCARE. Similarly, the record is devoid of any allegation that MANORCARE provided “unnecessary” medication to ZIMMERMAN. Under Scampone, evidence of survey deficiencies for patient falls and unnecessary medication are relevant because that evidence establishes “across-the-board substandard care”. As far as it goes, we do not quarrel with the Superior Court’s decision. However, we will stop short of declaring today that the survey deficiencies regarding patient falls and unnecessary medication will be admissible. The court in Scampone did not undertake a probative value versus prejudicial effect analysis with respect to evidence of survey deficiencies in areas not directly related to the Plaintiff’s harm. Because of this, we reserve the right to undertake undertake a probative value versus prejudicial effect analysis at trial as it relates to the survey deficiencies for patient falls and unnecessary medication.

The last, and most important, survey deficiency involves MANORCARE’s “infection control” programs. As a broad category, “infection control” implicates wound care and is absolutely at the heart of what PLAINTIFF is alleging in this case. We have little difficulty with the precept that inspection reports that reveal problems in a relevant area of concern are admissible to show that the Defendant had notice of those problems. See, e.g. Baker v. Ellis, 248 Pa. 64 (1915) (Elevator inspection report admitted to raise an inference that a dangerous condition was known to exist) and Fernandez v. City of Pittsburgh, 648 A.2d 1176 (Pa. Cmwlth. 1994) (City councilmen’s statement acknowledging existence of a defective road was admissible to show that the city had notice of a dangerous condition).

The dilemma presented to this Court is that the specific “infection control” problem identified at MANORCARE was that two housekeepers failed to properly wear gloves and/or wash their hands before entering and leaving the room of a man diagnosed with MRSA. The plan of correction imposed for this deficiency was “Facility staff will be in-serviced on infection control procedures related to isolation precautions.”

We do not know how facilities like MANORCARE should reasonably view survey deficiencies. Should the response to a deficiency be broad in order to encompass all facets of a deficiency, or is it enough that the facility addresses the specific incident that lead to the deficiency? We do not know the answer to this question.

Without question, “infection control” implicates the manner in which a facility like MANORCARE evaluates and responds to wounds such as the one suffered by ZIMMERMAN. On the other hand, nowhere in any of the PLAINTIFF’s expert reports is there any opinion or implication that violation of hand-washing and glove use protocols played any role in ZIMMERMAN’s harm. Under Scampone, the “infection control” survey deficiency is relevant – and we have little problem concluding that it is more relevant than the other survey deficiencies – but it does not implicate issues that were directly linked to any harm suffered by ZIMMERMAN.

As with the survey deficiencies pertaining to patient falls and unnecessary medication, we will be deferring a final decision regarding the infection control deficiency until the time of trial. At that time, we will undertake a “probative value versus prejudicial effect” analysis before rendering a final decision. We advise both parties in advance that we view the infection control deficiency as more relevant than the ones involving patient falls and unnecessary medication. Still, because the specific problem that gave rise to the infection control deficiency is not implicated by the facts of this case, we will defer a final decision until the time of trial.

- Understaffing

MANORCARE’s next Motion in Limine seeks to preclude argument or testimony concerning allegations of understaffing and/or under-budgeting. As a sub-component of this argument, MANORCARE asserts that PLAINTIFF’s expert nurse, R.N. Jessica Petka, should not be permitted to testify regarding issues of causation. Because the issue pertaining to Nurse Petka is different in many respects from the argument regarding understaffing, we will separate the two arguments for purposes of analysis. In this section, we will address MANORCARE’s request to preclude PLAINTIFF from arguing that MANORCARE’s Lebanon facility was understaffed.

All of PLAINTIFF’s experts have issued reports that criticize MANORCARE for failing to observe and/or identify the extent of ZIMMERMAN’s wound problems. PLAINTIFF’s theory is that MANORCARE neglected to observe and/or identify the extent of ZIMMERMAN’s problem because MANORCARE did not have enough trained staff to do so. According to PLAINTIFF, MANORCARE was understaffed because it elevated its own profits over quality of care.

MANORCARE strenuously refutes PLAINTIFF’s argument. MANORCARE points to objective staffing data known as HPPD data. According to MANORCARE, the Pennsylvania standard for staffing is 2.7 and MANORCARE met or exceeded that standard during ZIMMERMAN’s stay. MANORCARE complains that neither Dr. Mirza nor Nurse Petka are able to link any alleged staffing issues to deficiencies in ZIMMERMAN’s care. In its motion, MANORCARE states that PLAINTIFF “fails to correlate any facts of record to show a causal nexus between alleged understaffing and any harm to Mr. Zimmerman.” (ManorCare’s Motion at page 20).

We will not preclude PLAINTIFF from proffering its “profits over patients” theory. In Scampone v. Grane Heathlcare Co., 11 A.3d 967 (pa. Super. 2010), our Superior Court permitted a similar argument and stated: “the evidence of understaffing and insufficient care in question related to all residents of the nursing facility, including the decedent, and that the effects of the understaffing were specifically connected to decedent’s care.” See also, Hall v. Episcopal Long Term Care, 54 A.3d 381 (Pa. Super. 2012).

It is not the role of the Court to determine whether MANORCARE’s Lebanon facility was understaffed or under-budgeted; that is a decision that should be left to the jury. With this being said, we warn PLAINTIFF that our decision to permit him to pursue claims of understaffing and/or under-budgeting should not be viewed as a license to undertake a global prosecution of how MANORCARE conducted its business. To the extent that PLAINTIFF wishes to argue that MANORCARE was understaffed, PLAINTIFF will have to tie that understaffing to care – or lack of care – afforded to ZIMMERMAN.[6]

We will be denying MANORCARE’s motion to preclude PLAINTIFF from producing evidence and/or arguing that MANORCARE’s Lebanon facility was understaffed and/or under-budgeted. Provided that competent evidence is presented to support the claim, we will permit PLAINTIFF’s counsel to argue his client’s understaffing claim as part of a closing argument to the jury.

- Nurse Petka’s Opinion

PLAINTIFF proposes to call Registered Nurse Jessica Petka as an expert witness. Nurse Petka authored a twenty (20) page report. According to the preamble of the report, Nurse Petka possesses a Bachelor’s Degree in Nursing. She has worked in a “long-term acute care (LTACH) setting” as both a line nurse and a supervisor. Nurse Petka indicates that she has training and hands-on experience dealing with wound care.

In her twenty (20) page report, Nurse Petka is critical of the nursing services provided by MANORCARE. She opined that MANORCARE “demonstrated reckless disregard in their failure to assess and monitor [ZIMMERMAN].” Among her conclusions were the following:

- That MANORCARE’s staff failed to monitor and assess ZIMMERMAN’s foot skin on a daily basis;

- That MANORCARE failed to call a vascular physician to provide specialized care;

- That MANORCARE’s nursing staff failed to advise MANORCARE’s medical director about ZIMMERMAN’s condition; and

- That MANORCARE failed to provide “optimal pain management” for ZIMMERMAN throughout his stay.

Based upon her conclusions about the suboptimal care provided by MANORCARE, Nurse Petka concludes her report by stating:

“Nurses are aware of the risks when nursing standards of practice are not followed, and when not followed can cause serious harm to patients by the failure to provide prudent nursing care as in accordance to the standards of nursing practice. Nursing standards are set and accepted by nurses in accordance to prevent: The loss of limb related to the failure to perform daily comprehensive assessments related to residents like Mr. Zimmerman that had weak pedal pulses and edema to his lower extremities on admission and preventing an evaluation from a vascular physician in a timely manner, prevent infections, and provide education when a resident is refusing a medical treatment that could impact their health in a negative way (such as refusing to use his CPAP”…

It was foreseeable that William Zimmerman would be seriously affected from the devastating substandard nursing care and treatment or lack thereof.

It is my opinion to a reasonable degree of nursing certainty that the care, skill or knowledge exercised or exhibited in the treatment, practice or work that is the subject of this matter, was reckless and fell outside acceptable professional nursing standards. This conduct constituted willful and deliberate neglect and thereby, increased the risk of harm and was a cause in bringing about harm, and accelerated his deterioration of health to William Zimmerman.” (Petka’s report at page 20; emphasis supplied).

MANORCARE argues that no nurse can render an opinion regarding causation. Citing a section of Pennsylvania’s MCARE statute, MANORCARE argues that Nurse Petka “is not competent to provide testimony as to the causal link between the alleged understaffing and the vascular insufficiencies of Mr. Zimmerman.” (MANORCARE’s motion at paragraph 20).

Short- and long-term facilities for the elderly are commonly called “nursing homes” for a reason; the primary care provided at such facilities is rendered by Registered and Licensed Practical Nurses. Because of this reality, most litigation involving nursing homes includes expert testimony from professional nurses who have worked in an assisted living and palliative care environment. The dilemma for the courts is to define the scope and extent to which an expert nurse can provide testimony.

Pennsylvania’s MCARE law states:

“(b) Medical testimony – An expert testifying on a medical matter, including the standard of care, risks and alternatives, causation and the nature and extent of the injury, must meet the following qualification:

- Possess an unrestricted physician’s license in any state or the District of Columbia.

- Be engaged in or retired within the previous five years from active clinical practice or teaching.” 40 P.S. § 1303.512 (fee).

From this statute, it appears clear that Registered Nurses should not be permitted to render expert opinions regarding medical causation. But what should they be permitted to opine?

The issue of expert nursing testimony was the focus of appellate review in the so-called Freed litigation. Initially, the Centre County Court of Common Pleas prevented a Registered Nurse from providing expert testimony regarding the “causal connection between the alleged breach of the nursing standard of care and the development or worsening of a patient’s pressure wounds.” The Superior Court held that a Registered Nurse is qualified to testify that breaches in the standard of nursing care lead to development and worsening of pressure wounds. See¸ Freed v. Geisinger, 910 A.2d 68 (Pa. Super. 2006). Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court affirmed the Superior Court decision, citing a long-standing Pennsylvania common law principle that liberally facilitates the presentation of expert testimony. After re-argument was granted the Supreme Court affirmed their own decision. See, Freed v. Geisinger, 5 A.3d 212 (Pa. 2010).

The key opinion in the Freed litigation is the one authored by Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court on June 15, 2009. The Supreme Court acknowledged the existence of the MCARE limitation on testimony from non-physicians, and it even stated: “With this language, the MCARE Act expressly raised the standard for qualifying an expert witness in a medical professional liability action from that which existed under common law.” Id at page 1210. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court reasoned that a nurse has unique abilities to assess the care provided by other nurses. The Court stated:

“If a witness has any reasonable pretention to specialized knowledge on the relevant subject, he may be offered as an expert witness, and the weight to be given his testimony is for the trier of fact to determine…However, a nurse duly qualified under Rule 702 [Pa.R.Ev. 702], but licensed under 63 P.S. §216, is precluded from offering testimony on medical causation, while presumably a non-licensed nurse, or any other individual with the same knowledge or experience would be permitted, under the broad common law standard for expert testimony, to offer such testimony. Neither the Legislature nor this Court could have intended such an incongruous result.” Id at page 1210.

This ruling in Freed was softened considerably in a footnote. There, Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court recognized that its decision

“may have limited impact in light of the Legislature’s enactment of the MCARE Act, which became effective on May 19, 2002 and resulted in substantial changes in the requirements for qualifying an expert witness in medical professional liability actions….However, there are certainly situations in which it is questionable whether the MCARE Act will apply and thus [the Court] concludes [its] decision today retains its vitality. For example, the MCARE Act, by its terms, appears to apply only to medical professional liability actions against physicians, and not to other professional liability actions, or to actions against non-physician healthcare providers…” Freed supra at page 1212, Note 8.

Post-Freed Appellate decisions regarding expert nursing testimony provide limited guidance. In a non-precedential decision, Pennsylvania’s Superior Court affirmed a trial judge’s decision to preclude expert nursing testimony based upon MCARE. In Green v. Pennsylvania Hospital, 214 WL 10987745 (Pa Super. 2014), the Superior Court stated: “Appellant attempts to transform the discretionary language of the Freed footnote into mandatory language.” Rejecting this argument, the Court sided with approval the decision of the trial judge:

“Since the litigation involved liability against multiple physicians and nurses, it would have created an anomalous result to allow Pierce to testify as to causation as to the nurses, but claim he was incompetent to testify against the physicians for care that was in many places indivisible as to who was providing it. Therefore, the Court permitted Pierce only to testify ‘regarding his expert opinion of the quality of care provided by the defendant nurses but not as to causation of decedent’s death.’” Id

The Superior Court affirmed the trial judge’s decision. In doing so, the Court implicitly determined that MCARE precluded a nurse from testifying as to causation.

In the more recent case of Estate of Fabian, 222 A.3d 1143 (Pa. Super. 2019), the trial judge refused to qualify a Registered Nurse as an expert witness in a will contest. The Superior Court determined that this decision was an error. The Court stated that although the proffered expert lacked formal education on the issue at hand, the expert did have experience that afforded her with “specialized knowledge which would not otherwise be known to a lay individual.” Accordingly, the Superior Court held: “The Court’s reliance upon Nurse Young’s lack of formal qualifications was impermissible, and we hold that the Court’s refusal to qualify Nurse Young as an expert in the care of Alzheimer’s and dementia patients, therefore, was an abuse of discretion.” Id at page 1148.

The dilemma about the scope of an expert nurse’s proffered testimony is not confined to Pennsylvania. See, Annotation, Admissibility of Expert Testimony by Nurses found at 24 A.L.R. 6th 549 in cases cited therein.[7] However, our survey of law from across the country leads us to conclude that Registered Nurses will almost always be permitted to provide expert opinions regarding the standard of nursing care expected and whether those standards were breached. The question across America, as in Pennsylvania, is the extent to which nurses should be permitted to provide additional testimony regarding causation.

As a practical matter, it is difficult to separate standard of care from causation. When any expert professional renders an opinion regarding the expected standard of care, that expert will be required to support the opinion. Of necessity, the consequences of failing to provide a certain level of care represents a key factor – perhaps the key factor – in establishing what a standard of care should be. To prevent a nurse from explaining the potential consequences of failing to provide a certain level of care would be artificially limiting, and most juries would immediately recognize this fact.

If Nurse Petka is going to be permitted to provide testimony regarding the expected standard of care applicable to MANORCARE, and we believe she is so qualified, she will have to be able to amplify her opinion regarding standard of care with testimony that outlines the risks that accompany a failure to observe that standard of care. In this case, we will permit Nurse Petka to address those risks, even if they mirror what was actually experienced by ZIMMERMAN.

We will, however, draw a line that limits Nurse Petka’s ability to testify about causation related directly to ZIMMERMAN. We will not permit Nurse Petka to render an opinion about whether ZIMMERMAN’s leg amputation and subsequent death were causally related to any breach of nursing standards attributable to MANORCARE. To the extent that such testimony is necessary to get this case to a jury, the testimony will have to be provided by a licensed physician.

- Opinion as to Causation

Another component of MANORCARE’s Motion in Limine regarding understaffing and under-budgeting asks us to conclude that no one, including Dr. Mirza, should be permitted to draw a causal connection between ZIMMERMAN’s harm and MANORCARE’s alleged understaffing and under-budgeting. This is not a preclusion that we are willing to establish at this point in time.